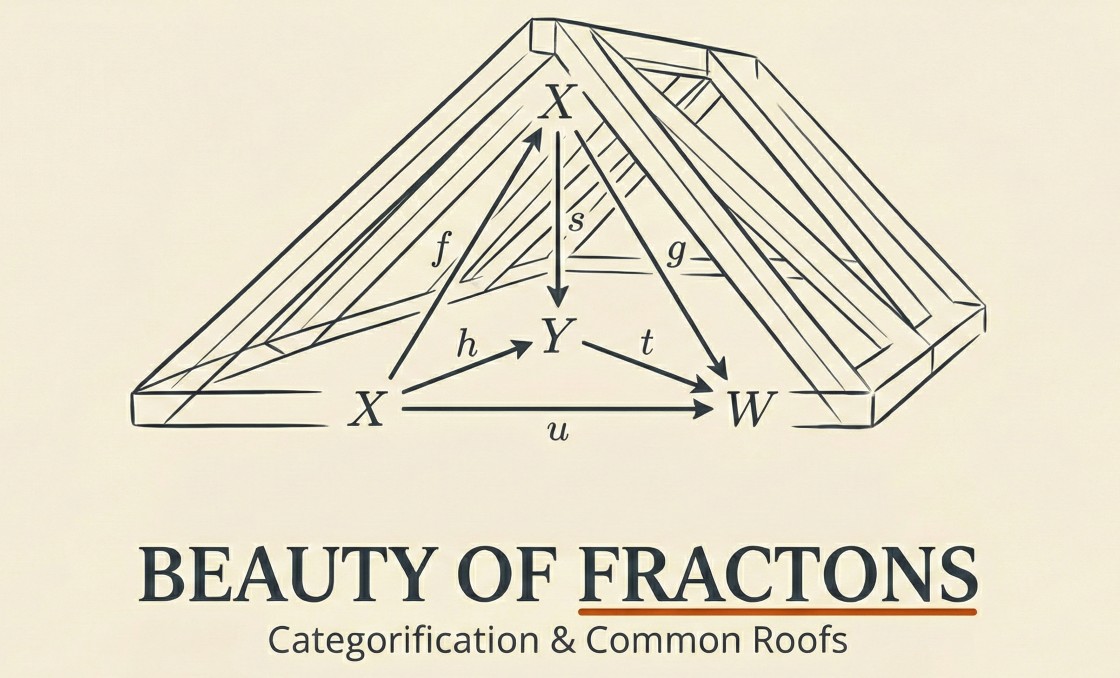

Fractions are deceptively difficult. I have seen many parents agonize over how to explain concepts like 1/4 or 2/5 to an eight-year-old without simply resorting to rote formal operations. Paradoxically, I only fully realized the complexity of basic fractions by taking a detour into deep theory. While reading Weibel’s An Introduction to Homological Algebra, I found a fascinating exposition on the categorification of fractions—known as localization.